KEEP IN TOUCH

Subscribe to our mailing list to get free tips on Data Protection and Cybersecurity updates weekly!

There are 160 apps on my phone. What they’re actually doing, I don’t know. But I decided to find out.

This is an English translation, read the original here.

I have a feeling these apps are spying on me. Well, not listening in, but that they’re keeping track of where I am at all times. That my every move is shared on. When I am shopping for groceries, having a drink, or hanging out with friends.

I know there are those that buy and sell such information. How are they tracking us, and what do they want with our data?

To try to get to the bottom of this, I started an experiment in February. I installed lots of apps on a spare phone. I would then carry that phone everywhere.

Or almost. I left it at home when I took a COVID-19 test in April.

There is a good reason for why my feeling of being monitored has increased over the years. This spring, I was part of an NRK team documenting how more than 8,300 mobile phones were being tracked while they were at hospitals or women’s shelters.

For the sum of 35,000 NOK (3,300 EUR / 4,000 USD), we got access to location data showing where tens of thousands of Norwegians had travelled in 2019.

One of them was 31-year-old Karl Bjarne Bernhardsen from Stavanger. The information made it easy for us to identify him in the data that – according to the data provider – had been anonymised.

When we called him, we could tell him where he had been nearly every day, through 2019. The Zoo. A job interview. At the hospital, where he stayed for several days as a first time new father.

– In the wrong hands this could be exploited by anyone, Karl said to us then.

It is a common refrain that commercial surveillance is not that scary: “It’s just used for ads.” But there are now many who are interested in the digital exhaust of our phones.

Recently the publication Vice Motherboard uncovered that the U.S. military buys location data and that a Muslim prayer app sent user location data to military contractors.

“It feels like a betrayal,” was the reaction from a local leader of the Council on American-Islamic Relations.

In 2018, the owner of an abandoned Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant was arrested in a border town in Arizona. He was supposedly involved in smuggling drugs from Mexico through a tunnel below the US border.

According to the Wall Street Journal (WSJ), the operation was in part uncovered due to U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) using commercially available location data.

Eventually, the commercial data was supposedly shared with the ICE arm in charge of deportations, according to WSJ.U.S. Customs and Border Protection (CBP) has also bought access to «global» location data.

Journalists in the NRK are asked to think twice before taking their phone along when meeting confidential sources for a reason. Authorities may get access to information about our whereabouts, even without court approval.

If my location data gets into the wrong hands, it may have consequences for others than myself. That is a constant fear – that someone who has told me something in confidence could get exposed.

The company that supplied ICE with the information about the fast food restaurant is called Venntel. According to company records they are located in an industrial cluster in the state of Virginia.

In the area you’ll find familiar names within the defence sector, like Lockheed Martin – the company behind the F-35 fighter, and Booz Allen Hamilton, Edward Snowden’s former employer. Take a 20 minute drive east, and you’ll be in Langley, Virginia, where CIA headquarters are locate

On August 20th, I requested a copy of all the information Venntel had about me. All Europeans have the right to do so, as a result of the GDPR, which was adopted in 2018.

The next day, the legal department of Venntel asked me to confirm some addresses I had visited recently.

“Once we have this information, we will first check to see if the Advertiser ID you provided is in our database,” the email said.

An «Advertiser ID» is something all smartphones have. This ID is the key to tracking phone users over time and across apps. Phone owners may limit how easy it is to access this ID, though few actually do.

I gave Venntel the address of my office at the NRK headquarters in Oslo, and to my flat at Majorstuen in Oslo.

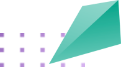

Almost a month later, I received an interesting email attachment from Venntel. It contained information on where I’d been 75,406 times since 15 February. Suddenly I could retrace my every step – on a hike, out for a drink, and visiting my grandmother in Southern Norway.

There were no phone numbers or names in the data. Still, it would have been easy for nearly anyone to find out that this was me. Simple searches in Google and the white pages would show there was a Martin Gundersen living in Sorgenfrigata in Oslo and working at NRK Marienlyst.

Venntel also informed me that they had shared my information with their customers. Their customers could use this information for purposes such as federal law enforcement and national security.

Who these customers were, Venntel declined to disclose.

How could my location data end up with Venntel in the US? None of the apps I had installed mentioned this company in any way. Nowhere. Not even in the impenetrable privacy policies hardly anyone bothers actually reading before clicking «OK».

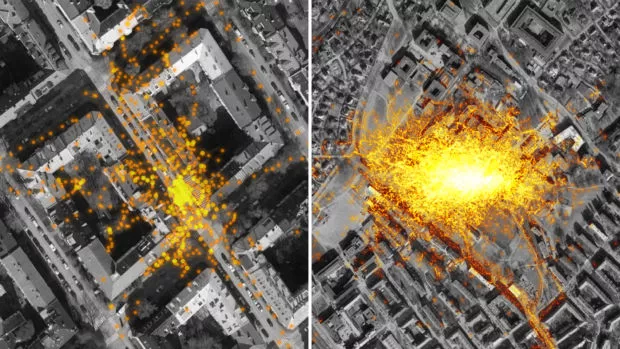

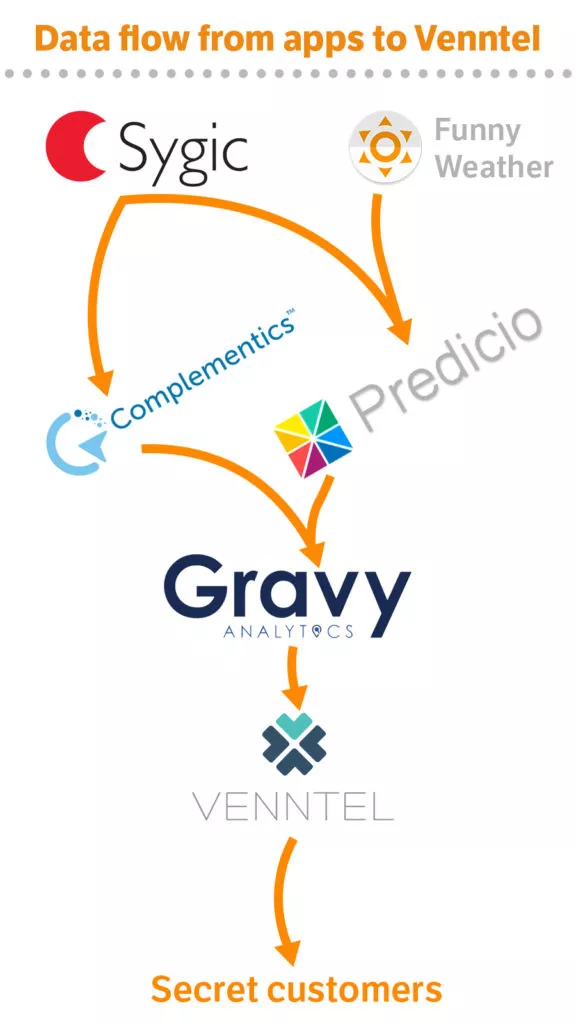

Venntel could inform me they had aquired my information from their parent company, Gravy Analytics, and that they only in a few cases knew anything more about which apps were involved.

Gravy Analytics is a data broker based in marketing. They collect vast amounts of data about consumers to improve ad targeting. Gravy Analytics also claims that they do not know the origin of most of the data. But the response to the request for access contained the names of two new companies: Predicio in France and Complementics in the U.S.

A new round of access requests uncovered that some of the location data that ended up at Venntel originated from a Slovak app developer called Sygic, which have a portfolio of 70 different apps.

Their most popular app supposedly has more than 200 million users, according to their webpage.

On 15 February, I installed two navigation apps from Sygic. Both asked me to consent to some terms for personalising my advertising experience.

If you are one of those who barely read what you consent to, you are not alone. Few actually read the terms of use of apps and services they install.

“I agree,” I pressed. We had now made a binding agreement, the app and I.

It appears that the agreement with Sygic was broken when Gravy Analytics received the data. Gravy Analytics stated in their privacy policy that my personal information could be used for a range of services for partners and customers. According to their own privacy policy, this included purposes such as fraud detection, law enforcement, and national security.

Put another way: Gravy Analytics shared my location data with their subsidiary company that specifically offered these kinds of services.

Which leads us back to my agreement made with Sygic on 15 February.

I have consulted with three lawyers, Malgorzata Agnieszka Cyndecka, Lee Bygrave, and Arve Føyen, who are all privacy specialists. They believed the fact that my personal information could be used for other purposes than I had agreed to was an apparent violation of the GDPR. Because GDPR is setting strict limits and requirements for what you actually can do with our personal information.

– This function creep is unacceptable. This practice is not only subverting the principle of purpose limitation, but also principles of transparency and fairness in GDPR, says Associate Professor at the Faculty of Law at the University of Bergen, Malgorzata Agnieszka Cyndecka.

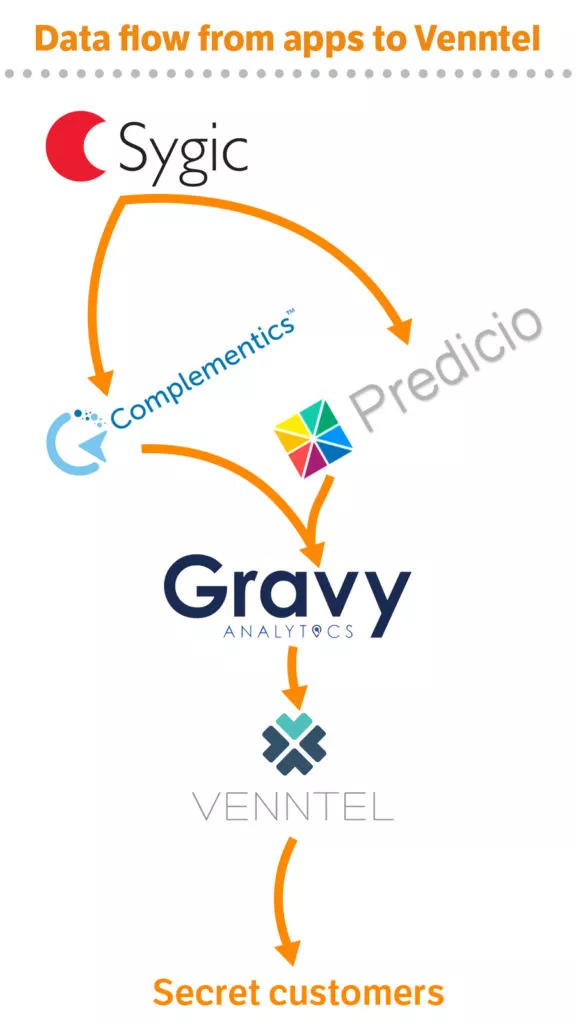

I was tracked by the weather app Fu*** Weather as well, according to the data files from Gravy Analytics and Venntel. The app promises to present the weather in a sarcastic, sharp-tongued manner. Because who wouldn’t rather have their daily forecast served with lots of profanities?

When installing the app this autumn, I agreed that my data could be used for analytics and «monetisation», ie. financing the app.

These same three lawyers I’ve consulted believe this agreement does not comply with GDPR, as it is too unclear what «monetisation» actually implies. Analytics also do not cover all of Venntel’s business practices.

Lawiusz Fras, the developer behind Funny Weather, does not have a large company behind him. He says he does not know Venntel, but states that he is open about the app’s business model.

«The fact that I cooperate with companies which utilize some data that the app has access to in order to make money of this is not confidential», Lawiusz Fras, the developer of the app writes to me in an email.

Fras admits the app could be clearer on what “monetization” entails. He intends to do something about this in the privacy policy, but maintains that users have been properly informed.

How the data from Funny Weather reached Venntel remains a mystery, but it is probable that the data flowed through the French company Predicio, as this intermediary is listed as a partner in the app’s privacy policy.

What other apps Venntel might be receiving data from is a well kept secret. Not even the people behind the mobile apps knew they were involved.

– We do not know the company Venntel, Zuzana Kacanova replies to my request on how my data ended up with them.

Kacanova claims that my consent had been lawfully obtained according to GDPR, and that their partners were contractually obliged to only use my data for marketing purposes.

– Based on the information you provided, it is not clear that the source of data Venntel has about you is Sygic GPS Navigation. If proven to be true, it is a breach of the contracts we have with the respective partners.

A technical analysis conducted by NRK shows several details indicating that data from Sygic has ended up with Venntel. For instance, an ID used by Complementics for data from Sygic is present in the data from Venntel as well.

Kacanova did not reply to questions about what consequences this will have for their partnerships with Predicio or Complementics.

With the arrival of GDPR in 2018, privacy advocates had won an important victory. The common European legislation was supposed to enable closer scrutiny of companies trading in user data. Yet, parts of the digital ad industry hasn’t changed much.

– They are trying to hang on to old practices and disguise them as something different, but are at the core still the same, David Martin says from his living room in Brussels.

He is leading the digital rights group in BEUC, an umbrella group for European consumer organisations. Parts of the digital advertising system is «built on an almost systemic breach» of the GDPR, according to Martin.

He is sharing the view of most privacy advocates: In theory, GDPR is great, but in practice it has serious shortcomings.

The Austrian privacy researcher and activist, Wolfie Christl, has for a number of years been investigating how companies use our data. Recently, he assisted the Norwegian Consumer Council with «Out of Control», a report documenting several potential privacy violations in the app ecosystem.

– In most cases, it is difficult or impossible to trace how personal data is flowing between apps, data brokers and their clients, he says.

To Christl, it appears the data protection authorities in the EU are either unable or unwilling to stop many of the breaches of the GDPR.

– We won’t see any change without massive fines and data processing bans. EU member states and the EU Commission must act, he ascertains.

The question is whether anyone is willing to listen. And how simple it would be to prosecute the alleged violations. Arve Føyen, partner in the legal firm Føyen Torkildsen, thinks it is difficult to penalise companies like Venntel, as they have no offices in Europe.

– I am afraid this is giving an illusory impression that the rules apply – but in practice, it’s just not possible to take legal action, Føyen explains.

Also Read: Data Protection Officer Duties And Responsibilities

Several months have passed since I brought my extra phone to the Ullevålseter sports lodge – a popular place for coffee and waffles in the Nordmarka forest.

On my screen I now see dots winding along forest paths. Several cluster together where I took a rest, where I walked briskly, they’re further apart.

It was a hot late summer Sunday. The horseflies were active, especially around the boggy stretches.

We tend to forget most places we have been and what we did there. Still, a couple of cues are enough for memories to return. Retracing my steps that summer Sunday became like leafing through an old album, where every page contains its own story.

The funny thing is, somebody else is holding this data. My movements.

It is uncanny to follow my own steps, even though they do not divulge any romantic affair, secret meetings, or embarrassing health issues.

Most of us have moments in our life we do not want to share. Not even to our closest, our bosses, or the government.

I was able to map the data flow from mobile apps to Venntel, but I still have a lot of unanswered questions. Which of Venntel’s customers acquired the information about me? Could it be companies in the defence sector, intelligence, the FBI?

Gravy Analytics did not response to our repeated inquiries. The subsidiary Venntel did not want to be interviewed by phone or email.

In a short statement, Venntel claims that my phone movements haven’t been shared with ICE or CBP. They also write that they have no relationship with the app providers Sygic or Lawiusz Fras. (NRK has never claimed they have a direct relationship, but has documented that the company is acquiring information from these apps via others.)

“We will not comment further on our business relationships or on interpretation of law”, Venntel writes.

In a statement given to the NRK, The United States Customs and Border Protection (CBP) states that they they have limited access to commercially available data, and that they are used in line with relevant rules and regulations. (you can find the entire statement at the bottom of this article).

CBP Press Officer Jason Givens did not reply to follow-up questions about what limitations are placed on the CBP in acquiring data on European citizens or phones that are outside the U.S. border zone.

FBI and ICE also have contracts with Venntel, but they have not answered questions about what opportunities it provides to track Europeans in and outside Europe.

When the Predicio responded to the request for access on 11 August, they did not mention anything about sharing data with Venntel between February and July. (The Funny Weather app was installed on August 10th.) Predicio has not responded to my repeated inquiries about interviews.

Also Read: EU GDPR Articles: Key For Business Security And Success

Complementics co-founder Walter Harrison states that my data was used only used for marketing analytics. Harrison did not want to be interviewed and he did not answer questions about their relationship with Gravy Analytics. When Vice Motherboard asked Harrison about Gravy Analytics, they said that its partner «has committed by contract that it will not share any data it receives from Complementics directly or indirectly with any U.S. government intelligence, immigration enforcement, or law enforcement agency».