KEEP IN TOUCH

Subscribe to our mailing list to get free tips on Data Protection and Cybersecurity updates weekly!

As QBot campaigns increase in size and frequency, researchers are looking into ways to break the trojan’s distribution chain and tackle the threat.

Over the past few years, Qbot (Qakbot or QuakBot) has grown into widely spread Windows malware that allows threat actors to steal bank credentials and Windows domain credentials, spread to other computers, and provide remote access to ransomware gangs.

Victims usually become infected with Qbot through another malware infection or via phishing campaigns using various lures, including fake invoices, payment and banking information, scanned documents, or invoices.

Ransomware gangs known to have used Qbot to breach corporate networks include REvil, Egregor, ProLock, PwndLocker, and MegaCortex strains.

Also Read: Things to Know about the Spam Control Act (Singapore)

Due to this, understanding how threat actors infiltrate and move in a Qbot compromised environment is critical for helping defenders stop intruders before they can unleash devastating attacks.

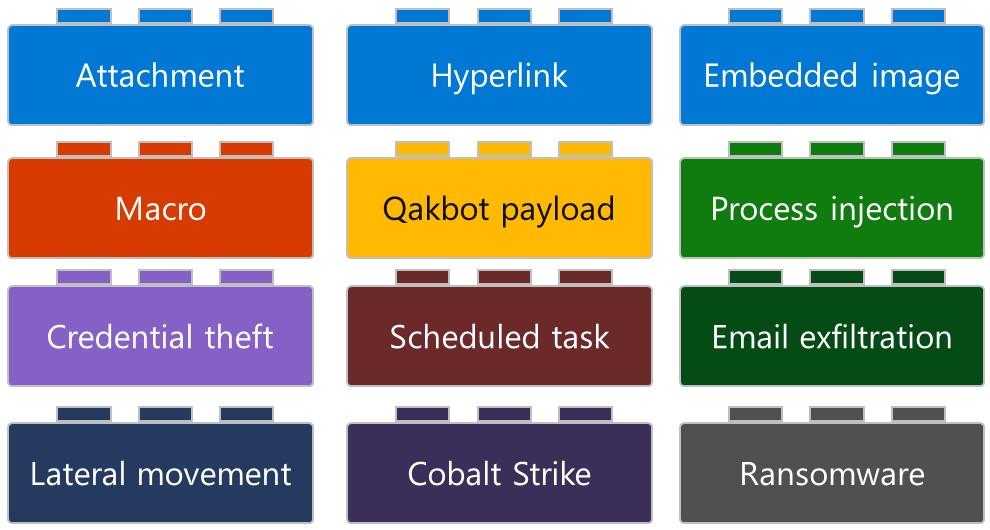

In a new report, Microsoft breaks down the QBot attack chain into distinct “building blocks,” which can be different depending on the operator using the malware and the type of attack they are conducting.

To illustrate an attack chain, Microsoft used Lego pieces of different colors, each representing a step in an attack.

“However, based on our analysis, one can break down a Qakbot-related incident into a set of distinct “building blocks,” which can help security analysts identify and respond to Qakbot campaigns,” explains the research by Microsoft.

“Figure 1 below represents these building blocks. From our observation, each Qakbot attack chain can only have one block of each color. The first row and the macro block represent the email mechanism used to deliver Qakbot.”

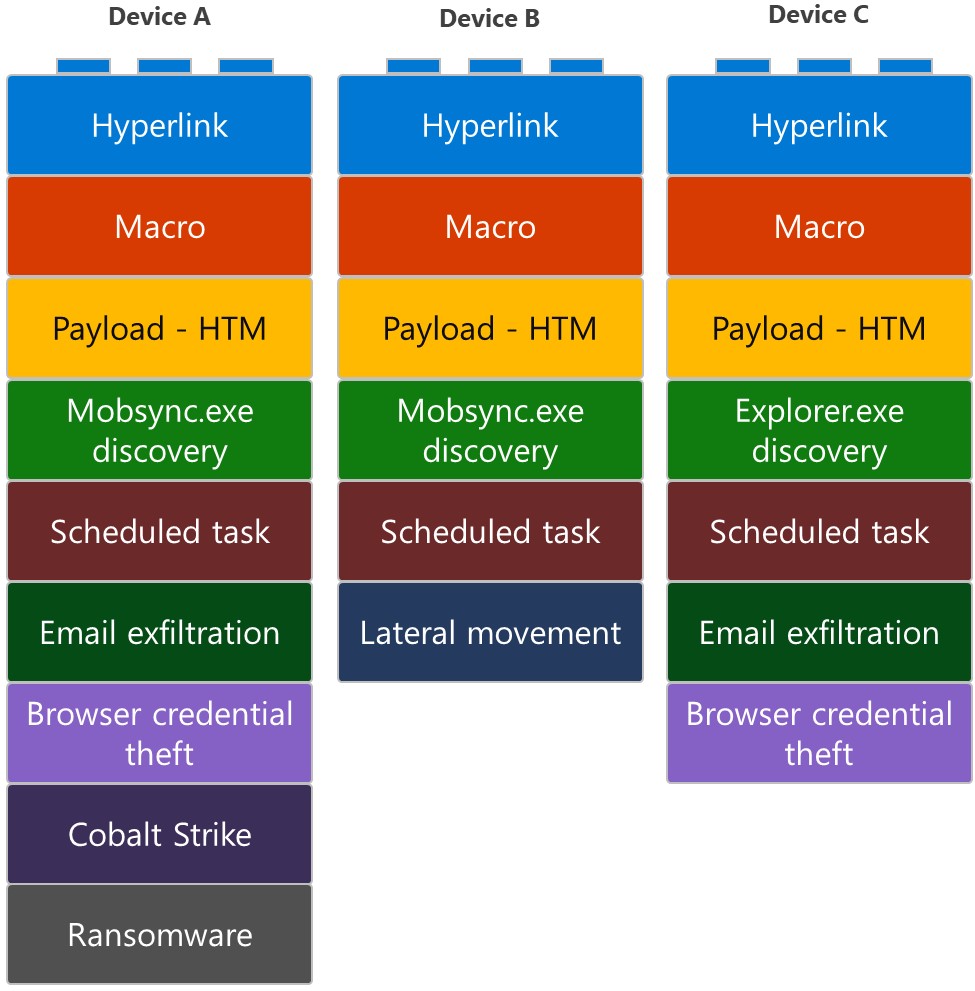

These different attack chains are either the result of a highly-targeted approach or an attempt to succeed in a single infiltration point by trying out multiple attack channels simultaneously.

Even when looking at three devices targeted in the same campaign, the attackers may use three different attack chains.

For example, Device A ultimately suffers a ransomware attack, while Device B is used for lateral movement, and Device C is used to steal credentials.

Also Read: The impact of GDPR and PDPA in Singapore

The use of different attach chains in the same attack underlines the importance of analyzing all evidence in post-attack investigations, as no safe conclusions can be drawn by looking into sample logs or what occurred on one device.

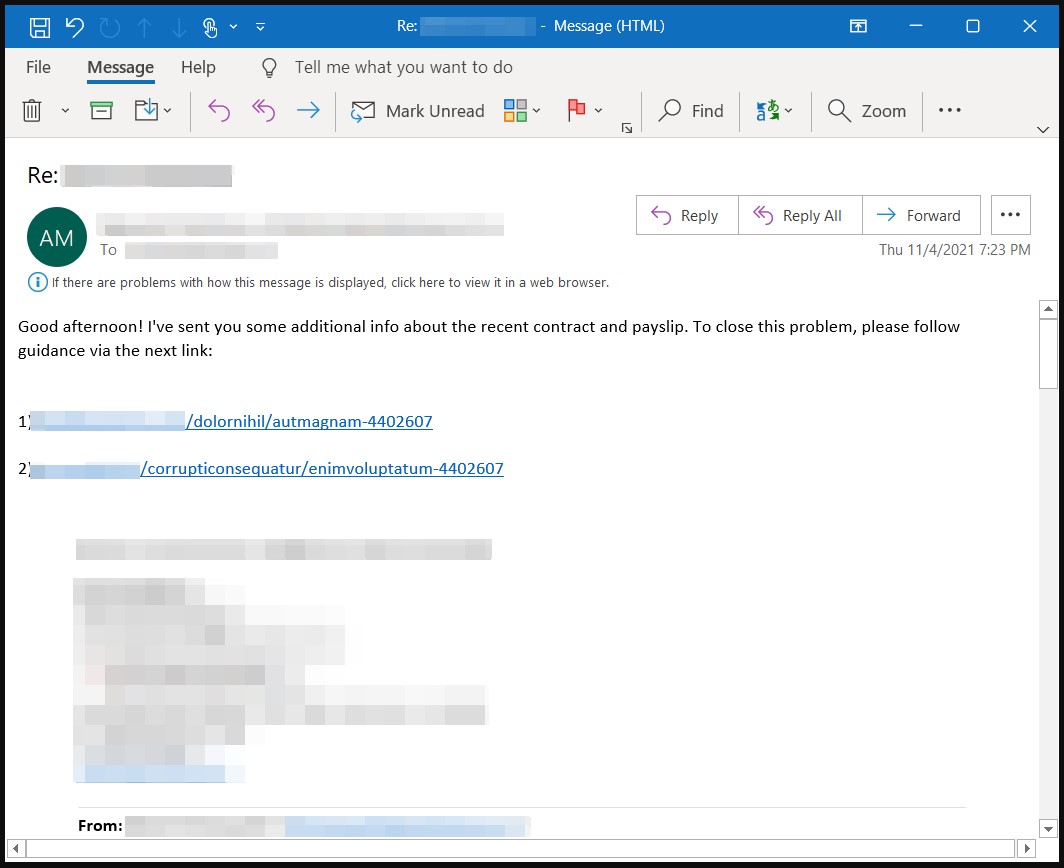

Whatever happens in later stages, it is essential to underline that the QBot threat begins with the arrival of an email carrying malicious links, attachments, or embedded images.

The messages are typically short, containing a call to action that email security solutions ignore.

Using embedded links is the weakest approach, as many are missing the HTTP or HTTPS protocol in the URLs, making them not clickable in most email clients. Furthermore, the use of non-clickable URLs is likely to bypass email security solutions by not being an HTML link.

However, recipients are unlikely to copy and paste these URLs on a new tab, so the success rates drop.

However, their chances get much better when the actors hijack email threads to construct a spoofed reply.

We’ve seen this type of internal reply chain attack working successfully against IKEA recently, and it’s particularly hard for security solutions to track and stop it.

In the cases of malicious attachments, the attacks are again weak because most security products would flag ZIP attachments as potentially malicious.

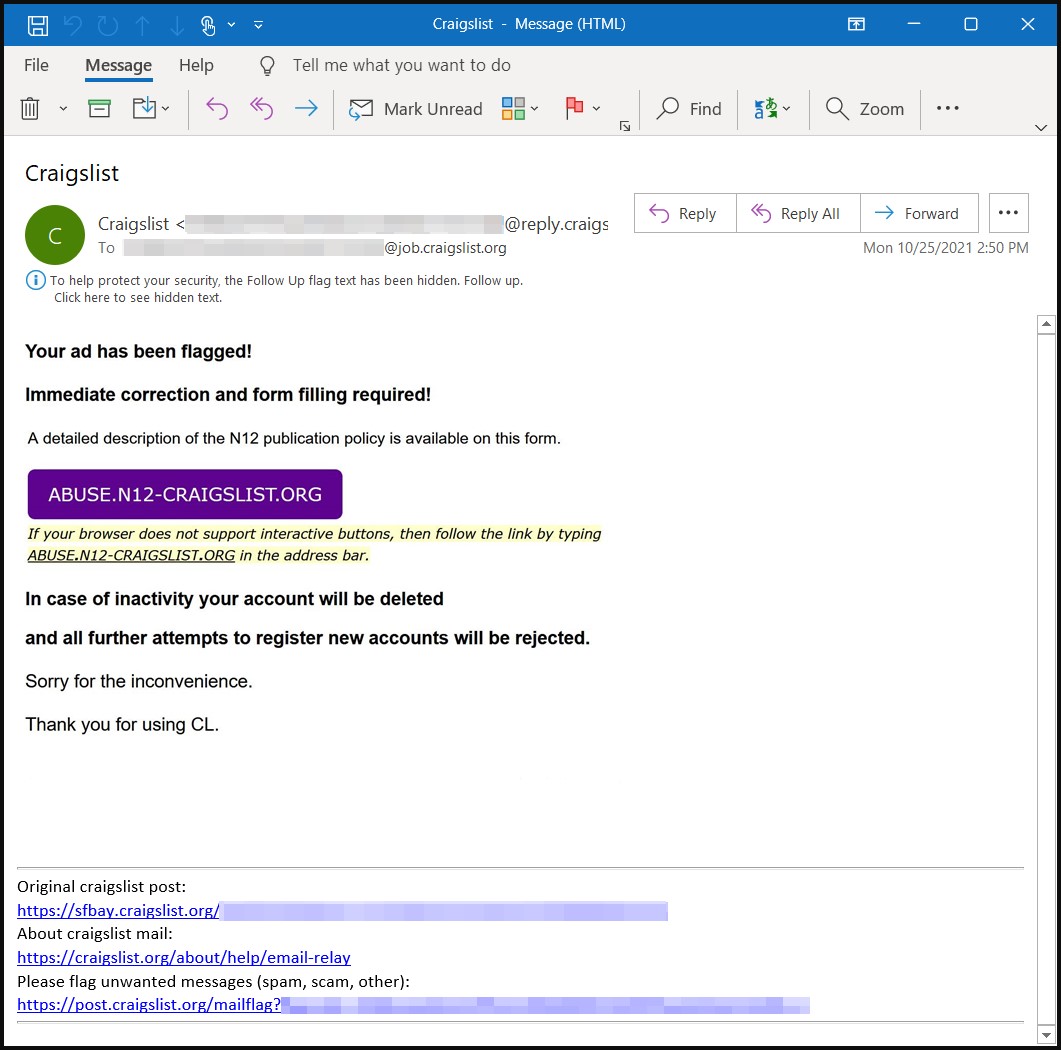

The latest addition in QBot’s delivery repertoire is embedded images in the email body, which contain the malicious URLs.

Again, this is another way to evade content security tool detection, as the image is a screenshot of text urging the recipient to type the link themselves.

Doing so results in downloading a laced Excel file that carries the malicious macros that eventually load QBot on the machine.

After the delivery of the email, Qbot attack chains use the following building blocks:

QBot distribution started spiking again in November 2021 and is helped further with the emergence of the ‘Squirrelwaffle’ attacks.

As QBot infections can lead to various dangerous and disruptive attacks, all admins need to become intimately familiar with the malware and the tactics it uses to spread throughout a network.

Since all infections begin with an email, it is crucial to focus your vigilance there, avoid clicking on unknown URLs or enabling macros, and provide employees with phishing awareness training.

For those interested in hunting QBot, Microsoft refreshes this GitHub repository with up-to-date queries frequently.